New to objkt: Pixel Symphony

“The goal is to create something that invites deeper reflection and connection.”

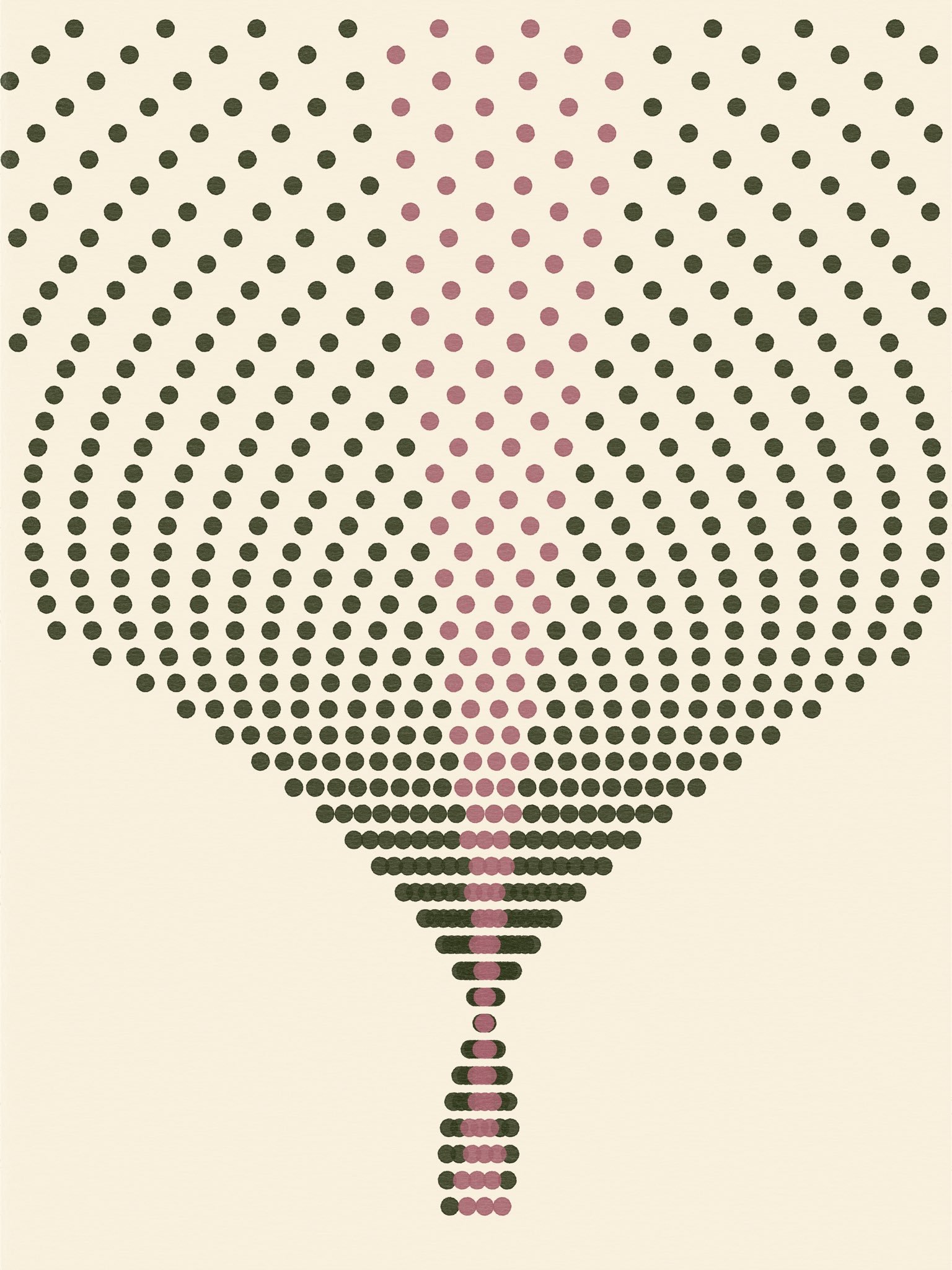

Poetics of Space #120. Owned by m/branson.

Piyush is his name, but if you're into generative art and fluent in web3, you might know him by his alias, Pixel Symphony. Based in California for over a decade with an engineering background, he carved his own path through art. His education spans Modern and Contemporary Art, Psychology, History and Religious Studies, and his work fuses geometric abstraction reminiscent of the suprematists with the emotive texture of abstract expressionism. “My practice today is rooted in design, structure, and abstraction, always with a strong conceptual foundation,” he explains in this interview for objkt MAG.

Pixel Symphony's work speaks to us in a singular way. With every series, he manages to synthesize the dialectics between mathematics and philosophy — and that’s exactly what makes his pieces so interesting. It is possible to see beyond the ever-present geometry, in all its essentiality.

We discussed Poetics of Space, his latest generative art release, which embodies that perspective of looking beyond mere form. Launched last Wednesday, January 29, on fx(hash) it also features the collection Ink & Paper, with 12 physical works on objkt, each plotted and signed by the artist.

The symbolism of the circle — or, as he defines it, self-referential signs — a closed system echoing Baudrillard’s notion of simulacra, invites reflection on a world where reality and representation blur. In its microcosm, each circle in Poetics of Space perpetually refers to another, erasing any sense of a stable or original form.

These ruptures in cycles, akin to the “events” envisaged by Badiou, compel us to reinterpret the entire system. As the artist suggests, “ultimately, one is invited to question how a form so emblematic of closure and completeness may, paradoxically, harbor the seeds of transformative disruption.”

Pixel Symphony — who debuted on objkt recently (in 2024, with the Polyphony series) — also talks about plotting, a practice that is an essential part of his creations, about colors, about books, about music. An artist's universe is invariably encapsulated in his works; within that space, there may lie an infinite expanse.

We can see a balanced duality, a dialectic between the concrete and the organic in your work. When you incorporate philosophy into the mathematical precision of generative art, is it something you plan in advance, or does the thought process come after the outputs emerge?

I love how you described that balance between the concrete and the organic — it’s something I think about often. For me, it’s never entirely planned or completely spontaneous. Both happen in parallel, and they influence each other throughout the process. I usually start with a conceptual anchor, whether that’s rooted in philosophy, aesthetics, or geometry, but once I begin writing and iterating the code, unexpected directions emerge. That’s when reflection kicks in — I look at what’s unfolding and allow the concept to shift or solidify naturally.

Space & Ego #81 - Owned by LoneWick.

For example, in my series Space & Ego, I had a clear starting point inspired by Max Bense’s ideas and my admiration for Manfred Mohr. I knew the questions I wanted to explore, and they guided the initial stages. But with Archetypes, it was more about exploring patterns and whether there’s a universal aesthetic embedded within mathematical principles. Waveforms in that series became more than just a design element — they turned into the central idea driving the whole exploration.

Then, there are projects like Poetics of Space, where I didn’t fully understand the concept until I had lived with the visual outputs for a while. What started as visual experimentation grew into something deeper through iteration and observation. That’s when I realized that the process itself is often the philosophical statement.

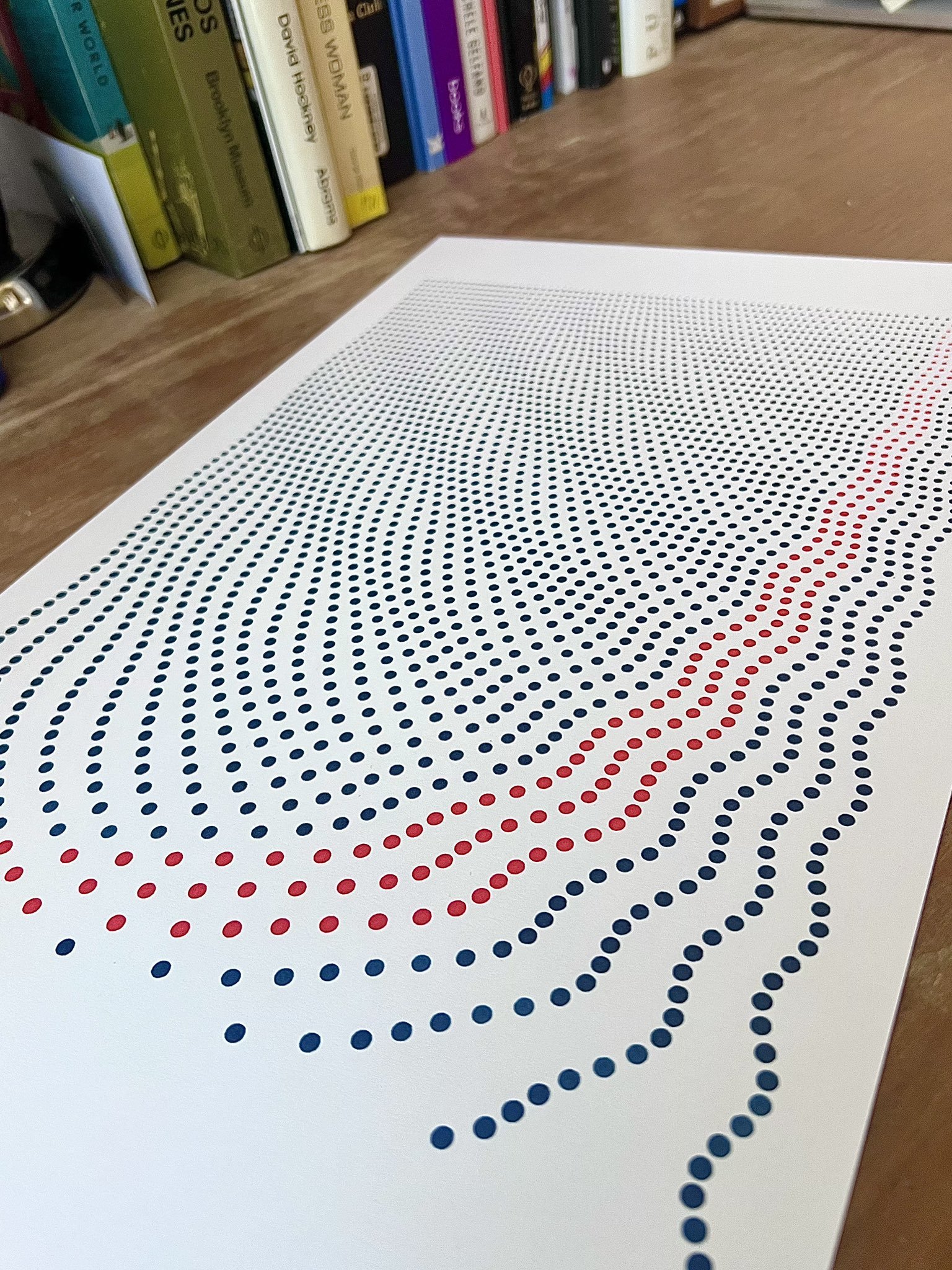

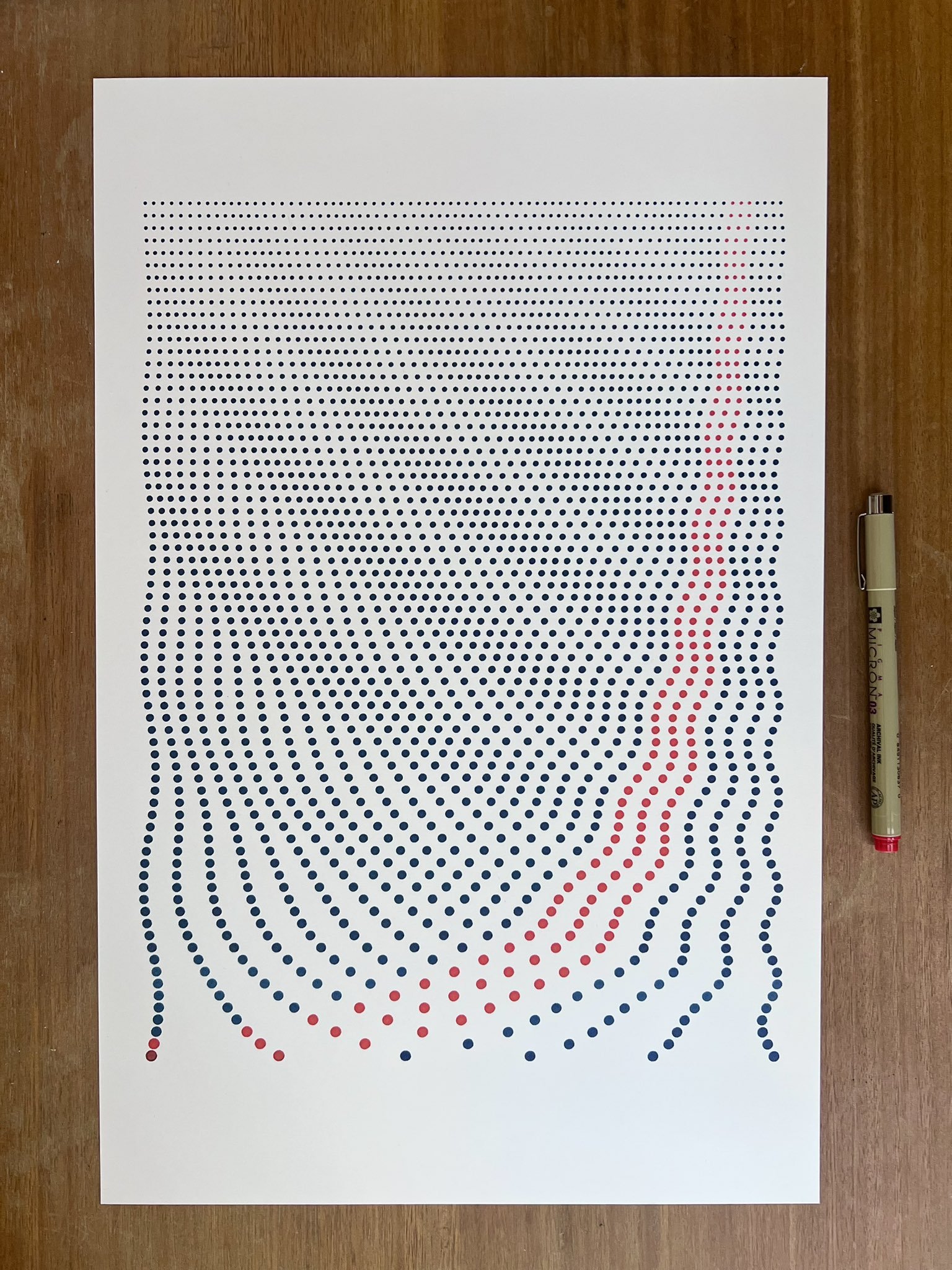

“For me, plotting isn’t just about preservation, though that’s part of it. It’s about making the work tangible, something you can live with and experience over time. ”

A significant part of your work is also redeemable in plotted versions. How do you view the transformation of digital art into physical form? Do you see it as a way of preserving the work, and do you worry about how your pieces might be accessed and experienced in the future?

Plotting is essential to my practice because it bridges the digital and physical in a way that feels personal to me. The plotter isn’t just a tool — it’s an extension of the creative process. Each plotted piece is like a physical artifact of a digital journey, capturing the imperfections and unique character of ink on paper.

For me, plotting isn’t just about preservation, though that’s part of it. It’s about making the work tangible, something you can live with and experience over time. I don’t worry too much about future accessibility — between blockchain technology and digital storage, there are plenty of ways to preserve and share the work. But the physical version offers something the digital can’t: permanence, texture, and the feeling of something crafted by hand.

Poetics of Space - detail.

About the selection of pieces for Poetics of Space: Ink & Paper on objkt — I’d like to know how this process works. It’s a kind of curation, right? I imagine it must be difficult for you, as the author of the complete work, to choose only a few outputs for this purpose. I suppose it’s similar to writing and then being your own editor, in a sense — cutting words, stitching the text together; in this case, the images. Is there an internal struggle, a tension between the artist and the curator in this process?

Yes, absolutely — the selection process is a form of curation, and it often feels like being your own editor. Each output holds meaning for me because they’re created throughout the evolution of the series, not just at the end. The works I listed as physical editions in Poetics of Space: Ink & Paper aren’t chosen from a finalized, static body. They’re the foundational, exploratory outputs — the "originals" that helped shape the series as it developed.

When I plot works during the creative process, I’m not just testing outputs for technical execution. These pieces represent key moments of discovery where I was refining ideas, responding to the algorithm, and making critical decisions that influenced the direction of the project. They’re not simply experiments — they’re milestones.

Once the series has reached a point of resolution, the more traditional curatorial role begins. I select works that represent the essence of the series — those that capture its evolution, highlight the most well-executed plots, and contribute to its narrative arc. It’s a mix of technical execution, aesthetic resonance, and conceptual alignment.

The process isn’t always easy. Some outputs that I feel personally attached to might not make the cut because they don’t fit the larger narrative. There’s a constant push and pull between the artist and the curator within me, but ultimately, I try to choose the pieces that are not only visually compelling but also integral to the story the series is telling.

“There’s something about the texture of ink on paper, the imperfections, the tactile quality — it grounds the work in reality.”

How do you think the context of displaying generative art (such as in a digital gallery or physical space) changes the way people experience it?

It’s fascinating how much context can change the way people engage with generative art. For me, that variability is one of the most exciting aspects of the medium — it can offer something different to each viewer depending on how and where they encounter it.

When I engage with my own work digitally, I don’t see it as isolated, standalone outputs. Instead, I experience it as part of a system, where each piece is a fragment of a larger conversation. I like to click through countless iterations, building a mental map of the series and how its elements interact. The digital space allows for that kind of exploration — it’s fluid, dynamic, and expansive.

But the physical space adds something unique. When I plot a piece and bring it into my living space, it changes the relationship entirely. There’s something about the texture of ink on paper, the imperfections, the tactile quality — it grounds the work in reality. Plotting also forces me to slow down and think about the permanence of each output in a way that the digital medium doesn’t.

I think viewers experience that duality too. Some people are drawn to the technical side, admiring the code and the system behind the visuals. Others connect more with the aesthetic or emotional impact. Generative art thrives on that range of experiences.

How do you decide which palette to use for a specific piece, and how does it tie into the emotions you aim to evoke?

Color is essential to my work, and I spend considerable time in each project carefully thinking about how color defines the tone and mood of the piece. It really appeals to my inclination toward design, where I often incorporate lessons from my study of art and design history. Color in generative art isn’t just a visual layer — it often becomes an integral part of the concept itself.

Appearance and Being #71. Owned by dist.cs.

For example, in my project Appearance and Being, one of the rare color palette combinations was inspired by Edith Young’s Color Scheme, a book I discovered at my local library. It featured diverse palettes drawn from various sources, and for this series, I selected and merged two: the deep tones of Vermeer’s pupils and the striking reds of Renaissance red caps. I also drew inspiration from masters of color, making the palette feel like a natural extension of the series’ conceptual dialogue. The colors, in this case, were more than aesthetic choices—they were part of the work’s language.

This ties into the physical aspect of my work as well. When plotting, I often test different pens, inks, and papers to see how they interact, feeding back into my digital palettes. However, I don’t always limit myself to palettes that are available physically; sometimes, digital offers freedom to explore combinations beyond physical constraints.

In my most recent project, Poetics of Space, I’ve taken a different approach, using earthy, pastel tones that reflect the project’s contemplative nature. Here, color serves as Badiou’s concept of the “Event” — a sudden rupture or shift that breaks the established rhythm and introduces something unexpected. In this way, color becomes not only an emotional tool but a structural one, driving the narrative forward and creating moments of tension and discovery.

“Machines can generate outputs or stumble upon novel combinations through randomization, but the creative spark that drives innovation and new movements — whether rooted in aesthetic, philosophical, or conceptual ideas — remains uniquely human. ”

Do you think it’s appropriate or problematic to classify AI-generated art as generative art? And in the case of “traditional” generative art, created by artists who program code or use node-based software, what is the role of the human component that the machine cannot replace?

To be honest, I don’t get too caught up in labels. Whether we call it AI-generated or generative art, what matters to me is that people understand what they’re experiencing and how it was created. Clarity is more important than rigid definitions.

The second part of the question resonates deeply with me because it touches on what makes generative art meaningful and, in many ways, timeless. Generative art, like all art movements, is part of a larger historical arc — an ongoing narrative of artistic exploration. For generative art to grow and remain relevant, it needs to continue adding original ideas to this shared artistic lineage. This is where human creativity becomes irreplaceable.

Metamorphosis #83. Owned by eritaqua.

Just as the Impressionists introduced groundbreaking techniques and ideas despite working with the same tools as their predecessors, today’s generative artists face a similar challenge. Machines can generate outputs or stumble upon novel combinations through randomization, but the creative spark that drives innovation and new movements — whether rooted in aesthetic, philosophical, or conceptual ideas — remains uniquely human. Machines can produce variations efficiently, but they cannot originate a sustained exploration of new ideas with a vision built on artistic history.

AI-generated art has its place, and it’s fascinating for what it can do. But in traditional generative art, the artist’s role is about more than just writing code — it’s about making intentional decisions, curating outputs, and framing concepts in a way that moves the art forward. Machines may assist, but the sense of aesthetic discernment and purpose comes from the human component, which, at least for now, cannot be fully replicated.

“ I find that the best stories I can tell often emerge through long form. There’s a sense of confidence and trust in your work that long form conveys—it reflects rigor, diligence, and a commitment.”

Short form or long form? Why?

Both formats have their strengths, and I often use them for different purposes. Short form is ideal for quick, iterative exploration, where immediacy and spontaneity drive the creative process. It allows for rapid experimentation and the ability to extract unique moments within a framework. Long form, on the other hand, offers the depth and space needed for more extensive generative processes and conceptual narratives.

Idle/Interludes #23. Owned by @andreasgysin.

That said, I find that the best stories I can tell often emerge through long form. There’s a sense of confidence and trust in your work that long form conveys—it reflects rigor, diligence, and a commitment. I find immense satisfaction when navigating a series that has both breadth and depth, with harmony. It feels like observing a vast, detailed canvas rather than a curated “best of.” Nothing compares to the joy of getting lost in a rabbit hole, uncovering subtle details that contribute to a larger whole.

What are the key challenges you face when trying to translate your thoughts into code, and how do you navigate the creative limitations that might arise from working in such a structured medium?

Translating abstract thoughts into code often involves a delicate balance between structure and intuition, and it’s a challenge that constantly evolves with each project.

In Poetics of Space, for instance, the translation process was sequential and intentional. It began with a simple arrangement of circles, iterating with small variations to see how they influenced the composition. As the project progressed, I transformed the array into a shifting, dynamic canvas and introduced color as a disruptive yet cohesive element. Color became more than just a visual layer—it acted as the spirit of the canvas, creating moments where the viewer’s perception shifted, inviting them to break from the static repetition of the form. This disruption was personal and intentional, guiding me toward the aesthetic that felt most complete while allowing the conceptual underpinnings of the work to emerge organically.

In contrast, Kosmos presented a different kind of challenge. As an extension of my earlier project Kink, it featured overlapping lines radiating from a central point. Here, I had less control over the outputs due to the inherent randomness embedded within the system, and I embraced that limitation. The unpredictability allowed for surprises, making the process more about discovery than precision.

Ultimately, this process feels like a constant push and pull, much like working in any medium. There’s always room to improve technical proficiency, but creativity itself is fluid and evolving. The core idea—whether it’s about form, color, or disruption—tends to transcend the medium, finding its way into the work regardless of the specific limitations.

What are you currently reading? Any books that have had a significant impact on your creative process lately?

I’m one of those readers who always has several books going at once. Recently, I’ve been focusing a lot on color, exploring both foundational texts and contemporary studies on the subject. On the essentials side, Albers’ Interaction of Color has again been a recent reference.

I’ve also been diving into the world of German Expressionism, sparked by a chance find—a beautiful book of prints from the period that I came across in a store in Healdsburg, CA. The book, The Graphic Art of German Expressionism by Lothar Günther Buchheim, has been a delight to explore. The darker, more subdued, and expressive palettes of this movement have likely influenced my choices in Poetics of Space.

On a different note, I’ve recently picked up a fascinating book on the history of India, though I’m still in the early stages of it. Lastly, I’ve finally begun reading Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke, a book that’s been on my list for ages (magic!).

“There’s definitely a subconscious connection between music and the creative output. I can look back and associate specific periods of my artistic development with the music I was immersed in at the time. Patti Smith’s Kimberly, for instance, always reminds me of when I was studying Cézanne intensely, playing Horses on loop.”

What kind of music are you listening to while you work, or when you’re just relaxing? Do certain genres or artists influence your art?

Jazz, particularly hard bop, is a staple for me — Blakey, Monk, and Mingus and the likes often play in the background when I’m working.

I also revisit grunge regularly. Indian classical music is another favorite, especially when I’m in need of something meditative and grounding. Lately, I’ve been listening to The Smile’s second album.

There’s definitely a subconscious connection between music and the creative output. I can look back and associate specific periods of my artistic development with the music I was immersed in at the time. Patti Smith’s Kimberly, for instance, always reminds me of when I was studying Cézanne intensely, playing Horses on loop.

Recently, you joined the objkt platform with your Polyphony series, minting two pieces, one of which has two plotted editions. Can you guide us through the creative process and philosophy behind this piece? Are there more to come?

The Polyphony series emerged from my ongoing exploration of lines and their expressive potential. The first work in the series channels Paul Klee’s vision of the line as a living entity—jittery yet deliberate, dynamic yet grounded. Coded in p5.js, the lines mimic the imperfections of hand-drawn strokes, capturing a balance between precision and organic movement.

Klee has had a profound influence on how I think about lines. His line drawings, with their raw simplicity and ability to convey both effortlessness and dexterity, have long inspired me. The line, as the most fundamental building block of any plot, features prominently across much of my work, but in Polyphony, it becomes the centerpiece, allowing for layered, rhythmic compositions that reflect my fascination with iterative design.

I certainly plan to revisit and expand this series. It’s one of many ongoing threads within my practice that hasn’t yet found its conclusion. Like much of my work, Polyphony exists as part of a larger creative entanglement — one that I look forward to returning to when the time is right.

Dive deeper at: www.pixelsymphony.art

Pixel Symphony profile on objkt: objkt.com/@pixxel